My great-aunt was one of the last passengers to travel on the Harlem Valley Railroad. It was spring 1972. I greeted her as she climbed off the train in Copake Falls–a journey that started at Grand Central. It wasn’t a comfortable ride. The line up from Brewster was light on passengers and heavy on freight.

Before 1940, active rail lines knitted together the manufacturing and farming towns of Columbia, Dutchess, Berkshire and Litchfield counties. One line provided a direct east-west route from Hartford or Springfield to Millerton and Poughkeepsie. Another line connected Hudson, Chatham, and Pittsfield. Smaller lines meandered through farms where bottling stations and creameries emerged.

Though the rail lines were a convenience for local dairy farmers and passengers, the railroad owners rarely made any profit.

Many assume that the Hudson River line is the grand-daddy of all routes north from Manhattan. In fact, the Harlem line was the first to be first conceived. It was envisioned as the primary route to connect New York City to Albany, the gateway to the Erie Canal and western expansion. As early as 1830, engineers determined that a route through the Harlem Valley was the most economical

Though construction began in 1833, the tracks didn’t reach the Roe Jan area until 1852. Since funding was provided by the New York State Legislature, routes were politically charged and construction was often delayed. Meanwhile, the enterprising river towns raised capitol to construct the Hudson River Railroad.

The impact of the Hudson railroad on the economy of the river towns was enormous. Industry and population swelled for generations.

It was somewhat different on the Harlem line. Though Millerton and Chatham benefited as they became intersections for multiple lines, Hillsdale saw a modest increase in population after the railroad came through. The hamlet grew from 20 to 60 dwellings between 1860 and 1870, including three stores, two hotels, and a population of about 300.

During the Civil War, the Harlem Railroad was used to transport local iron ore to munitions factories in Albany and Troy. But local agriculture was the real beneficiary of the new railroad. Sheep outnumbered cows three to one as the demand for wool increased. By 1875, Hillsdale was consistently among Columbia County’s top producers of wool, hay, buckwheat and butter. After Chatham, Hillsdale had the busiest station in the county.

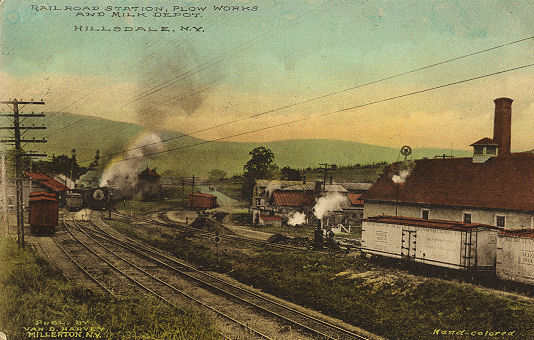

The growth of the New York City market for hay, butter, and other products stimulated Hillsdale’s economy. Farmers shipped milk directly to the city from trackside milk platforms. Columbia County’s first milk depot was built in Hillsdale in 1890 as a receiving plant where all the farmers could bring their cans of milk for bottling and direct shipment to New York. Within a few years, many of the surrounding railroad hamlets in Copake and Ancram also had milk depots. In 1900, local bottling was discontinued and all the milk was shipped in cans to a central bottling facility near East 96th Street.

Over the next few decades, dairying continued to thrive as creameries and cooperatives emerged up and down the line. By 1940, 90 percent of Hillsdale’s 103 farms reported dairy cows, the highest percentage of any town in Columbia County.

The local railroad had another role. Before the Roe Jan School opened in September 1933, students often hitched rides on the daily milk trains back and forth to the Hillsdale High School. It stood just up the hill from the depot on the corner of Main Street and Brady Lane. After a fire destroyed the building around 1920, students moved to the Mount Washington House for classes. According to some Roe Jan School graduates, the practice of hitching a ride to school on milk trains continued into the 1950s.

After the war, as farmers installed bulk tanks in their barns and hired trucking firms to transport their milk, traffic on the Harlem Valley Railroad declined to a trickle. Local passengers, as well as city folks who vacationed or had second homes here had little use for the Harlem railroad. Passenger travel was eliminated north of Millerton in 1972. The Upper Harlem Line was abandoned in 1976 and the track removed between Wassaic and Millerton and on northward to Chatham by 1981.

But that isn’t the end of the story. Learn more about the Harlem Valley Rail Trail.

by Peter Cipkowski

This 1912 fire insurance map (below) of the station area displays a world that no longer exists. Is it a blueprint for the future? It shows a passenger station, rail-side hotel, a milk depot (on the left, connected to its adjacent ice pond by a ramp for ice transport), a general store, a foundry and plow company, a feed store, and a lumber yard.

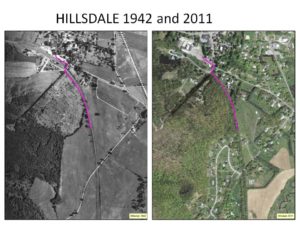

Pretty much the same area of the Hillsdale Station in an aerial photo from 1942 and 2011:

Here’s promotional map for the Regional Harlem Valley Railroad: